AMEDEO MODIGLIANI BIOGRAPHY

Dedo is how Modigliani was known in Livorno, Italy, before he moved to Paris.

Amedeo Modigliani had a lot going. He was Italian and had all the charm, verve and sexy mannerisms that make Italian men irresistible. He was Jewish and it gave him the extra chutzpah, the historical depth, the cultural awareness. He lived in Paris which by itself was an achievement—the only place to be in his day—for any artist destined to succeed. He was good looking. He loved women and they passionately loved him back.

There was something else. He was an extraordinarily inspired artist who painted people in such a way that he made them all look great.

By contrast, Picasso, who also lived in Paris at the time, made everyone look ugly, distorted, retarded, mangled up, disfigured.

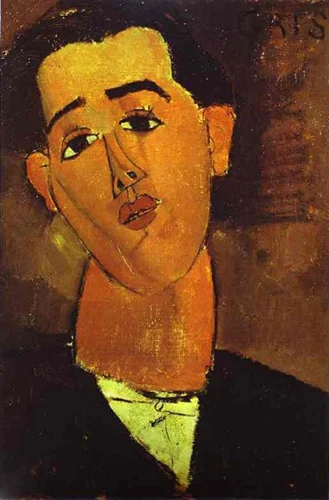

Modigliani made us love everyone he painted. Look at his portrait of Chaim Soutine:

Portrait of Chaim Soutine, 1917, courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

His immense compassion and tenderness for those he met is emotionally expressed in every one of his portraits.

Modigliani touches us. He makes contact with our humanity.

If you think you may own a Modigliani painting, drawing or sculpture, we believe we offer the most competent services in the world to authenticate it, appraise its value, or sell it.

Childhood

Amedeo Clemente Modigliani was the fourth child born into a Jewish family on July 12, 1884 in Livorno, Italy. His great-great grandfather had immigrated to Livorno in the 18th century to escape religious persecution like many other Jews during that time. Modigliani was the son of Flaminio Modigliani and Eugenia Garsin. Flaminio was a moneychanger, and when his business failed, his family was forced to live in poverty. Because of an ancient law, Amedeo, before he was even born, was able to save his family from ruin. According to this law, creditors could not take the bed of a pregnant woman. When creditors came to take Modigliani family possessions, Eugenia went into labor with Amedeo, and the family piled as many of their belongings onto the bed as they could in order to keep them. Amedeo had two brothers and one sister. Amedeo’s father died at a young age, so he was not around for most of his childhood.

In order to make ends meet Eugenia taught English and French, as well as other subjects in her home. She taught Amedeo at home until he was 10 years old. He was a sickly child and was plagued with health problems throughout his life. He suffered from pleurisy when he was 11 years old. At the age of 14 he developed typhoid fever, and in 1900, when Modigliani was 16, he contracted tuberculosis. Soon after contracting tuberculosis, he suffered another case of pleurisy. While feverish from typhoid, Modigliani ranted about wanting to see the paintings in the Palazzo Piti and the Uffizi in Florence. Eugenia promised her son that she would take him when he was well enough. Modigliani drew and painted from an early age and thought himself already a painter before having done any formal training. When Modigliani was well enough to travel, his mother kept her promise, and took her son to see the paintings of the Palazzo Piti and the Uffizi. She then took her son on a tour of southern Italy to see Naples, Rome, Amalfi, and Capri.

As a young boy, Modigliani was introduced to the philosophical ideas of Nietzsche, Baudelaire, Carducci, and Conte de Lautreamont by his maternal grandfather, Isaco Garsin. The writing of Lautreamont and Les Chants de Maldoror was also popular with the Parisian Surrealists, Modigliani’s contemporaries. Modigliani was so enamored with Les Chants de Maldoror, he memorized it. He continued to read and allow these ideas to influence his art. In 1901, Modigliani wrote to his friend and fellow art student, Oscar Ghiglia, from Capri while recovering from tuberculosis. Ghiglia served as a sympathetic ear to Modigliani’s ideas that “the only true route to true creativity was through defiance and disorder.”

When Modigliani and his mother returned to Livorno from Capri, Modigliani began neglecting his schoolwork to paint. He also frequented the local quarry to sculpt. Eugenia enrolled her son with the master painter Guglielmo Micheli. Modigliani received his earliest instruction in Micheli’s studio from 1898 to 1900. This instruction consisted mainly of styles and themes from 19th century Italian art. This influence can be seen in Modigliani’s earliest Parisian paintings. Micheli’s genre was so popular and unoriginal for the time that Modigliani rejected it. Micheli encouraged Modigliani to paint outside as the Impressionists did, but Modigliani didn’t enjoy painting “en plein air” or in cafes. He preferred to work indoors in his own studio and chose a proto-Cubist style similar to Cezanne.

Modigliani studied nudes, landscapes, portraiture, and still life under Micheli. It is with the nude that Modigliani blossomed. This talent may have been perpetuated by the fact he was intrigued by his housemaid. Micheli nicknamed Modigliani “Ubermensch” because he was such a skilled artist and often recited from Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

Adulthood

In 1902 Modigliani began studying at the Accademia Di Belle Arti and the the Scuola libera di Nudo (Free School of Nude Studies) in Florence where his teacher was Giovani Fatori. A year later he moved to Venice to study at the Istituto di Belle Arti and joined the Venice School of Nude Studies. It was during this time that Modigliani began to visit seedier parts of town to smoke hashish instead of studying. These self-destructive tendencies may have been ignited by the radical ideas of Nietzsche. From 1903 to 1906 Modigliani worked in Venice, and the Biennale introduced him to Art Nouveau and Impressionism.

In 1906 Modigliani traveled to Paris, the focal point of the avant garde and artistic universe. The artists Gino Severini and Juan Gris also arrived in Paris about the same time. Modigliani lived at several different addresses during his stay in Paris. At Le Bateau-Lavoir, a community for poor artists in Montmartre, he rented a studio in Rue Caulaincourt, which he decorated with Renaissance reproductions and plush draperies. He wrote his mother regularly and spoke of how he met Picasso, but disapproved of his uncivilized appearance, even if he was a genius. He also met Georges Braque and Max Jacob. Jacob became Modigliani’s best friend. His mother had sent enough money with Modigliani to last a few months, if he was careful. Modigliani was never very careful with money.

Photo of Modigliani as a young man

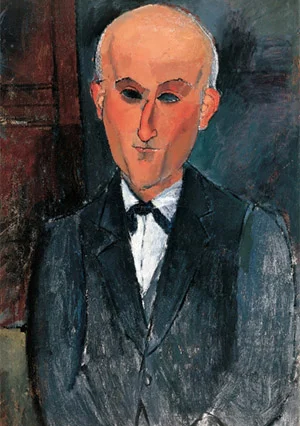

Portrait of Max Jacob

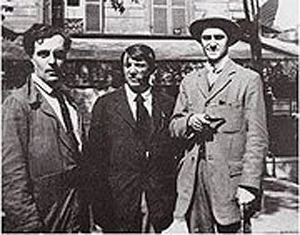

Photo of Modigliani, Picasso, and Salmon

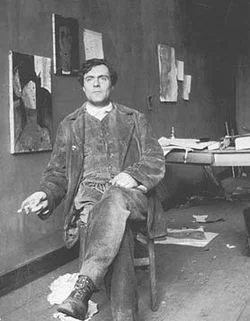

Photo of Modigliani in his studio

Modigliani was described by his contemporaries as a bit reserved and almost asocial when he first arrived in Paris. He dressed as a debonair, academician artist, and he drank in moderation. Within a year his behavior had transformed from debonair artist, to prince of vagrants. When Louis Latourette, journalist and poet, visited Modigliani’s once pristine art studio, it was in a state of chaos. Modigliani was now an alcoholic and drug addict, and the state of his studio echoed this. He had become disgusted with all of his bourgeois trappings, his studio becoming the object of resentment he felt towards the academic art that symbolized his career. Modigliani destroyed most of his early work. His excuse for doing this was, “Childish baubles, done when I was a dirty bourgeois”.

It is speculated that Modigliani’s self-destructive behavior may have resulted from his tuberculosis and knowing that this disease would eventually kill him. His remedy was to enjoy life while he could by indulging in self-destructive behavior. His conduct was noticed even in Bohemian settings. His daughter, Jeanne Modigliani notes, “some people nearly swooned at his suave, cultivated manner, while others found him “an unbearable buffoon” and a “boring, drunken spoilsport.” He had frequent affairs and drank heavily, using absinthe and hashish.

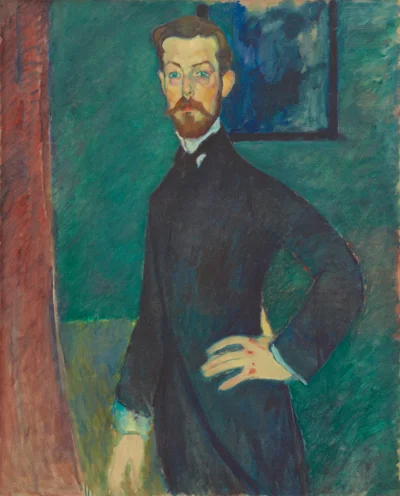

Portrait of Paul Alexander,Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan, 1909

He became the personification of the tragic artist, in the same the ranks as Van Gogh.

His early years in Paris were marked by a frenzy of work. He sketched as many as a hundred drawings a day, most of which he deemed inferior and destroyed, left behind when he moved, or gave to girlfriends. He was influenced by the works of Toulouse Lautrec and Cezanne, but eventually developed his own style that cannot be grouped with any other artist.

In 1907, Modigliani showed 7 watercolors and oil paintings in the Salon d 'Automne and 5 works in the Salon des Independants in 1908. This was quite an achievement for a young artist just arriving in Paris. He didn’t receive much attention from his exhibitions, and Modigliani’s frustration turned him to sculpting again. The sculptor Constantin Brancusi, his friend and neighbor, reignited this passion in Modigliani.

From 1901 to 1914 Modigliani carved a series of large stone heads even though the dust was not good for his lungs. These heads had long, slender noses and tiny lips. Modigliani received his first patron during this time, Paul Alexandre, a young surgeon, who also wanted to be an art dealer. Alexandre ran a cheap art colony in a dilapidated house on Paris’ Rue du Delta. He allowed Modigliani to live there rent-free in exchange for paintings. Alexandre paid Modigliani the equivalent of about 40 to 80 dollars per painting. Modigliani painted 3 oil portraits of Alexandre from 1909 to 1913.

Portrait of Anna Ahkatomova, courtesy of RuriC, Switzerland, 1911

In 1910 Modigliani met his first serious love, Anna Akhmatova. Akhmatova had a studio in the same building as Modigliani. Modigliani was 26, she was 21, and she was married. They began an affair that lasted about a year when Anna decided to return to her husband. Anna personified Modigliani’s aesthetic idea of perfection. It is also during this time that Modigliani’s portraits begin to take on the features of his stonework.

The influences on Modigliani’s work during this time may have been African masks and Cambodian art on exhibit at the Musee de l'Homme. Modigliani had also been exposed to Mediaeval sculpture while studying in Northern Italy. The subjects of his paintings and sculpture take on elements reminiscent of ancient Egyptian art: almond shaped eyes, curved noses, and elongated necks. These same characteristics can be observed in the Mediaeval sculpture and paintings of Modigliani’s native Italy. In 1913, Modigliani’s abstract sculptures and paintings became more intricate and symmetrical in design, incorporating curves and geometric patterns. His figurative work echoes that of Botticelli's in its elegant elongation of the female body. Mason Klein, associate curator at the Jewish Museum in New York, feels that “Modigliani’s keen awareness of being a Jew and a foreigner allowed him to be more accepting of the richness of non-Western art.”

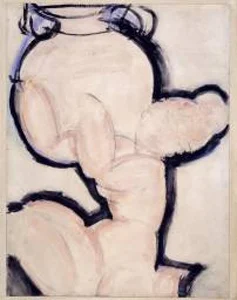

Sketch Caryatid, 1914, courtesy of the Tate Collection, Britain

Portrait of Madame Pompadour (Beatrice Hastings), 1915, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL

In 1914 Modigliani met the very eccentric English poet, Beatrice Hastings. She became his mistress and often the victim of his drunken rampages. Hastings was a haughty and pompous woman, as well as a proud feminist, writer, and literary critic. Modigliani nicknamed her Madame or madam Pompadour because of her arrogance. In 1915, Modigliani painted a series of 14 portraits of Hastings. They lived together till 1916, but because of contrasting personalities, their relationship lasted only 2 years. During this time Modigliani created his most powerful paintings, for example the Portrait of Juan Gris.

Portrait of Juan Gris, 1915, courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Portrait of Leopold Zborowski, 1916

In 1916, Modigliani became acquainted with Polish poet and art dealer, Leo Zborowski, and his wife, Anna. Zborowski gave Modigliani a studio and hired models for him to paint. The following summer, Russian sculptor, Chana Orloff, introduced Modigliani to Jeanne Hebuterne, a beautiful 19 year old art student. Hebuterne was from a very conservative, bourgeois background. Her Roman Catholic family disapproved of Modigliani, whom they perceived to be little more than an immoral vagrant, and worse than that, a Jew. Modigliani and Hebuterne were soon living together. Their relationship was tumultuous, and their public arguments became more famous than his public drunkenness. Despite their clashes, Modigliani always introduced Hebuterne as “his best beloved,” an endearment he never used with the other women in his life. Apparently Hebuterne’s love for Modigliani was unconditional because she said she didn’t mind his drinking and bar hopping.

Photo of Jeanne Hebuterne

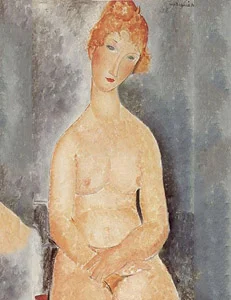

Seated Nude, 1918, Honolulu Academy of Arts

On December 3, 1917, Modigliani had his first solo show at the Berthe Weill Gallery. This gallery was located across the street from a police station. When the police inspector noticed the activity at the gallery, he went over to check things out. The inspector was horrified at Modigliani’s nude paintings displaying body hair. He forced Modigliani to close the exhibit just hours after opening.

San Sebastiano; Building in which Modigliani's Venice studio was located.

After the German bombing of Paris in 1918, Zborowski organized an artist retreat to Nice for Modigliani and a few other artists. This retreat lasted nearly a year. Modigliani tried to sell his work to wealthy tourists visiting Nice, but managed to sell only a couple of pieces for a few francs each. Despite his disappointment, Modigliani proceeded to create the paintings that would later become his most famous works. Modigliani sold only a small number of his works during his lifetime, and never received much for any of them. The money he did receive went quickly for his drug habit. It is said that a landlord confiscated Modigliani’canvases for unpaid rent and used them to patch mattresses.

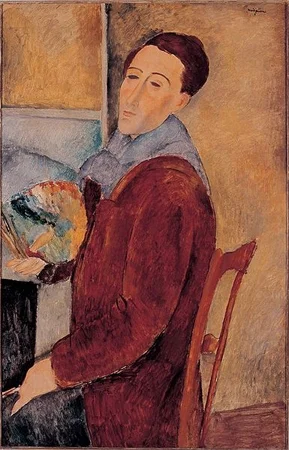

Self-portrait, 1919 Museu de Arte Contempor�nea da Universidade de S�o Paulo, S�o Paulo, Brasi

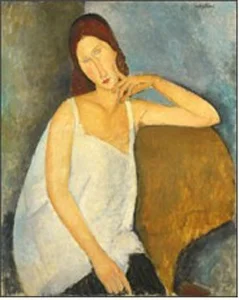

Jeanne H�buterne, 1919, oil on canvas, courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Nate B. Spingold, 1956

During his time in Nice, Modigliani’s palette grew brighter, and his compositions grew bolder. On November 29, 1918, Hebuterne gave birth to a baby girl they named Jeanne, after her mother. By the summer of 1919 Hebuterne was pregnant again, and Modigliani’s art was being shown in a major London exhibit.

In May 1919, Modigliani returned to Paris with Jeanne and their baby daughter. They rented an apartment in the Rue de la Grande Chaumiere. While living there, Modigliani and Hebuterne painted portraits of each other and of themselves.

In 1920 Modigliani made this entry in his sketchbook, “A new year. Here begins a new life.” This was written three weeks before his death. He realized he was dying, but continued to paint right up until the end, despite his alcoholic blackouts.

Photo of Jeanne Hebuterne

A worried neighbor came to check on them one day and found a delirious Modigliani holding on to Jeanne who was almost nine months pregnant. Modigliani was taken to a charity hospital where he died two days later on January 24, 1920 of tubercular meningitis, an incurable disease at the time. Modigliani’s funeral was attended by many of his colleagues from the artistic community in Montmartre and Montparnasse. He was buried in Pere Lachaise Cemetery. Art dealers eager to buy Modigliani paintings approached the mourners. The price of his paintings skyrocketed, and forgeries flooded the market.

Livorno, Italy, where Modigliani was born. Photo by Etienne; Creative Commons.

Hebuterne was taken to her family’s home, but was inconsolable. Two days later she threw herself out the 5th story window of her family’s home, killing herself and her unborn child. Because Hebuterne’s family blamed Modigliani for her death, she was buried at Cimetiere de Bagneux near Paris. Her family had a change of heart 10 years later and reburied her beside Modigliani.

Modigliani died penniless, having only one solo exhibition in his lifetime and giving his work away in exchange for rent and meals. The only inheritance left for his fourteen month old daughter was a collection taken up by his friends. Neither did Modigliani’s family in Livorna receive anything from his death. Hebuterne’s family later released paintings and artifacts of her life with Modigliani. His sister, Margherita, who lived in Florence, adopted Modigliani’s daughter. Jeanne Modigliani later wrote a biography of her father titled, Modigliani: Man and Myth.